Introduction

The sweeping tax reform enacted in December 2017 will significantly increase the tax cost of executive compensation in publicly held corporations where the compensation for each of the top five executives exceeds $1 million. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that these corporations will reduce the executive compensation to offset the increased tax cost, which will likely be shifted to public shareholders.

This Essay shows that this significant tax cost is not transparent to shareholders. Our analysis of a hand-collected dataset of relevant proxy statements that were filed in the first fifty days after the enactment of the tax reform reveals that companies do not provide their shareholders with sufficient information about the tax cost of executive compensation.

Therefore, there is a need for a prompt regulatory response. To make the tax cost of executive compensation fully transparent, this Essay proposes that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) should adopt new disclosure requirements, outlined in this Essay, as soon as possible. The disclosure of the tax cost of executive compensation would significantly improve the accuracy of investor information regarding the overall cost of executive compensation, and it could enhance shareholders’ ability to scrutinize compensation practices, all while imposing minimal compliance costs upon firms.

I. The Tax Cost of Executive Compensation

In general, under section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code, 1 Unless specified otherwise, all references to sections are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended. a publicly-held corporation cannot deduct from its taxable income compensation exceeding $1 million to the chief executive officer (CEO), chief financial officer (CFO), or the other three highest-paid executive officers. 2 26 I.R.C. § 162(m)(1) (2016). These top executives are referred to as “covered employees.” See id. § 162(m)(3). Although the $1 million deduction cap was originally enacted by Congress back in 1993, it was easily avoided by structuring remuneration as performance-based compensation or deferred post-employment compensation, which were exempted from the deduction limitation under the old section 162(m). 3 The old section 162(m)(4)(C) provided the exception for performance-based compensation. Id. § 162(m)(4)(C). Under the old section 162(m)(3), a person could be a “covered employee” only during the employment period, and the post-employment compensation was not subject to the deduction limit. Id. § 162(m)(3).

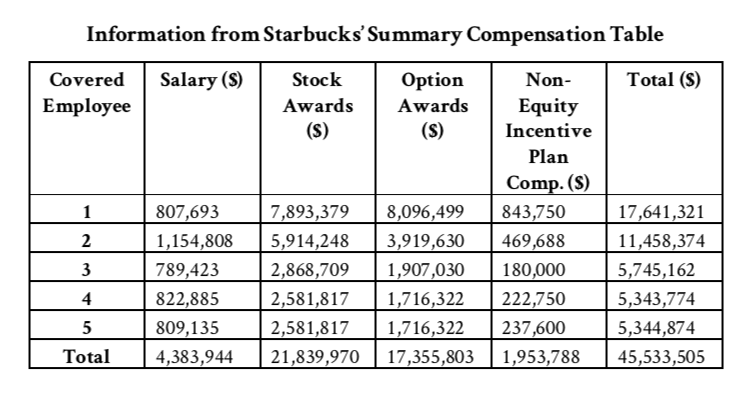

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) 4 Act of Dec. 22, Pub. L. No. 115-97, 131 Stat. 2054 (2017) [hereinafter TCJA]. Although the act was originally introduced in Congress as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the act ultimately passed under the title “To provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for the fiscal year 2018.” See Eli Watkins, Senate Rules Force Republicans to Go with Lengthy Name for Tax Plan, CNN (Dec. 19, 2017, 10:14 PM EST), https://perma.cc/GK73-86HJ. This Essay refers to the 2017 tax legislation under its original name. repealed these widely used exemptions as a revenue-raising measure. 5 TCJA § 13601(a)(1) repealed the exception for performance-based compensation; TCJA § 13601(b)(3)(C) expanded the definition of “covered employee” to include any person that was a covered employee in any preceding taxable year beginning after December 31, 2016. For the estimated revenue effects, see Joint Comm. on Taxation, Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, The “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” 5 (2017). This amendment followed previous reform proposals. For more details about the previous proposals, see Michael Doran, Uncapping Executive Pay, 90 S. Cal. L. Rev. 815, 844 (2017). The TCJA also expanded the category of companies that are subject to the deduction cap. 6 26 I.R.C. § 162(m)(2). The TCJA expands the companies subject to section 162(m) to include corporations with publicly traded debt and foreign companies publicly traded through American depositary receipts. See TCJA § 13601(c). These changes will substantially increase the tax cost of executive compensation. Take Starbucks, for example. The following information was obtained from Starbucks’s recently published proxy statement for the 2017 fiscal year 7 See Starbucks Corporation, Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A), at 38 (Jan. 26, 2018). :

Starbucks did not disclose how much of the nonsalary compensation was deductible under the old section 162(m); the proxy statement noted, however, that nonsalary compensation was designated as performance-based compensation, 8 See id. at 27. which should, in principle, be eligible for deduction under the old section 162(m). If all nonsalary compensation qualifies as deductible performance-based compensation under the old section 162(m), then only salaries that exceed $1 million should not be deductible. Thus, the disallowed deduction in 2017 should be approximately $154,808, and the tax cost of this lost deduction should be $54,182. 9 This figure is the disallowed deduction multiplied by the corporate tax rate in 2017 (35%).

Under the amended section 162(m), all compensation exceeding $1 million per executive is not deductible: The disallowed deductions should be approximately $41,304,369, and the tax cost should be approximately $8,673,918, 10 This estimate assumes that if these expenses were deductible they would be deducted against taxable income at the tax rate of 21%, which is the applicable tax rate for corporations under the TCJA. about 266 times the cost under the old section 162(m). This new tax cost would mean that Starbucks’ executive compensation would become approximately 20% more expensive. 11 It is also important to note that before 2018, when a corporation deducted the compensation expenses against income taxable at 35%, only 65% of the cost of the compensation impacted the corporation’s after-tax profits. Post-TCJA, the impact of executive compensation on the corporation’s after-tax profits is much higher.

Starbucks is not alone. Most large companies in the United States grant their CEOs compensation that exceeds $1 million. 12 See David F. Larcker & Brian Tayan, CEO Compensation: Data Spotlight 2 (2017), https://perma.cc/2F89-8CL9. The median pay for CEOs of companies included in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index in 2016 was $10,817,000, 13 See Aubrey E. Bout & Brian Wilby, S&P 500 CEO Compensation Increase Trends, Harv. L. Sch. F. on Corp. Governance & Fin. Reg. (Oct. 7, 2017), https://perma.cc/B63J-D4RR. and many other named executives in these companies also received compensation that exceeded $1 million. 14 CEOs receive approximately three times the compensation of other named executive officers (NEOs) in the company. See Larcker & Tayan, supra note 12, at 8. Since the base salary of these CEOs constituted only 11.3% of their overall compensation in 2016, the tax cost under the old section 162(m) is relatively small. 15 See Matteo Tonello, CEO and Executive Compensation Practices: 2017 Edition, Harv. L. Sch. F. on Corp. Governance & Fin. Reg. (Oct. 4, 2017), https://perma.cc/LZQ3-3YRX. These changes in tax law are therefore expected to significantly increase the tax cost of executive compensation in a large number of companies. 16 Cf. Matthew Goforth, Tax Reform and the Effect on Equity Compensation, Equilar (Jan. 23, 2018), https://perma.cc/89KR-9R2Q (“The [TCJA] also ended the performance-based exemption to IRC Section 162(m) and expanded the pool of employees to which it applied . . . .”).

The TCJA provides a transition rule under which the amendments to section 162(m) do not apply to compensation under written binding contracts that were in effect as of November 2, 2017, if the contracts are not materially modified or renewed after that date (these arrangements are referred to as “grandfathered arrangements”). 17 TCJA § 13601(e)(2). This rule means that until all the grandfathered arrangements expire over the next few years, many companies will be subject to both the old and new rules. Once these grandfathered arrangements expire, however, the tax cost of executive compensation will attain its full magnitude.

II. Companies’ Possible Reactions

In the previous Part, we discussed the increased tax cost of executive compensation under the recent U.S. tax reform. Public companies might not remain indifferent to these tax law changes and could adjust both the level and the composition of executive compensation as a result. For example, public companies could reduce the overall level of compensation to offset the increased tax cost. They could also restructure compensation packages by substantially reducing the performance-based elements of executive pay. The increase in the fixed portion of the compensation could, in turn, enable companies to reduce overall compensation. This Part discusses these two possible responses and explains why they are unlikely to substantially change compensation practices and pay levels.

A. Level of Compensation

Theoretically, public companies could reduce or completely avoid the tax cost under section 162(m) by reducing executive compensation in excess of $1 million. As explained below, however, it is unlikely that companies will voluntarily adopt this approach. 18 Doran, supra note 5, at 841-42 (predicting that repealing the exceptions under the old section 162(m) “would further encourage directors and managers to ignore the deduction limitation and, thus, likely would increase still more the economic burden on workers and investors”).

First, many companies will likely argue that to attract and retain top managerial talent, they must incur the higher tax cost without reducing compensation levels. Partners from the leading law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz recently expressed their thoughts about companies’ expected reactions to the amended section 162(m): “This change will result in a significant increase in disallowed tax deductions. Nevertheless, we expect that companies will accept this result as a necessary consequence of the competitive marketplace for talent.” 19 See Jeannemarie O’Brien et al., Compensation Season 2018, Harv. L. Sch. F. on Corp. Governance & Fin. Reg. (Jan. 9, 2018), https://perma.cc/CX5K-YM5X. Some scholars have also expressed the view that the competitive market for managerial talent drives the level of compensation in public companies. 20 The view that executive compensation is a reflection of supply and demand in the competitive labor market for executives has been expressed by prominent financial economists. See, e.g., Xavier Gabaix & Augustin Landier, Why Has CEO Pay Increased So Much?, 123 Q.J. Econ. 49, 64 (2008) (“The pay of a CEO depends not only on his own talent, but also on the aggregate demand for CEO talent . . . .”); Bengt Holmstrom & Steven N. Kaplan, The State of U.S. Corporate Governance: What’s Right and What’s Wrong?, 15 J. Applied Corp. Fin., Spring 2003, at 8, 19 (noting that “[CEO] wages[] are ultimately set by supply and demand”); see also Steven A. Bank et al., Executive Pay: What Worked?, 42 J. Corp. L. 59, 96-101 (2016); Steven N. Kaplan, CEO Pay and Corporate Governance in the U.S.: Perceptions, Facts, and Challenges, J. Applied Corp. Fin., Spring 2013, at 8, 13-14. Others suggest that weak corporate governance allows executives to influence their own pay and that they use that power to extract economic rents. 21 See, e.g., Lucian Arye Bebchuk & Jesse M. Fried, Executive Compensation as an Agency Problem, 17 J. Econ. Persp. 71, 73-76 (2003); Noam Noked, Can Taxes Mitigate Corporate Governance Inefficiencies?, 9 Wm. & Mary Bus. L. Rev. 221, 255-56 (2017); David I. Walker, A Tax Response to the Executive Pay Problem, 93 B.U. L. Rev. 325, 332-34 (2013). According to both sides of this debate, there are forces—the labor market or managerial power—that would oppose a decrease in executive pay. Indeed, we are unaware of any public company that has so far expressed a clear intent to reduce executive compensation to offset the impact of the new tax rules. 22 See the review of the proxy statements in Part III below. A recent study by the Center of Economic and Policy Research provides additional support to our prediction that companies are unlikely to reduce executive compensation in order to minimize the tax cost under section 162(m). See Jessica Schieder & Dean Baker, Does Tax Deductibility Affect CEO Pay? The Case of the Health Insurance Industry 10 (2018), https://perma.cc/Q7C9-VSB2. The research used a provision in the Affordable Care Act, which prevents health insurers from deducting CEO pay in excess of $500,000. Id. at 1. This change effectively raised the cost of CEO pay, in excess of the $500,000 cap, to the company by more than 50%, on average. Id. However, the research found no evidence that limiting the deductibility of CEO pay for health insurers lowered this pay relative to other industries, after controlling for other determinants of pay. See id. at 10.

Moreover, companies might focus on the good news that they now pay a lower overall corporate income tax because of the general tax rate reduction under the TCJA. A recent publication noted that “for many companies, lost tax deductions will be effectively wiped out by lower overall corporate rates under the new code.” 23 See Goforth, supra note 16. The view that the tax benefit from the lower corporate tax rate “wipes out” the higher tax cost of executive compensation overlooks the fact that companies can avoid the higher tax cost of executive compensation by lowering the compensation. The focus on the overall tax savings might be used by managers, especially in poorly governed firms, to increase their compensation by shifting a portion of the tax savings to themselves.

B. Composition of Compensation

By exempting certain types of compensation from the deduction limit, the old section 162(m) created incentives for companies to adopt performance-based compensation plans, including stock options, stock appreciation rights (SARs), and deferred postemployment compensation. Under the amended section 162(m), there is no tax preference for any type of compensation arrangement. This may result in more companies increasing their nonperformance-based compensation. For example, it was recently reported that Netflix will replace its cash bonuses with higher salaries. 24 See Alicia Ritcey & Jenn Zhao, Netflix’s Cash Bonuses Become Salary Thanks to New Tax Plan, Bloomberg (Dec. 29, 2017, 7:32 AM PST), https://perma.cc/JC9R-8ZM6.

It remains to be seen whether compensation schemes will become less tied to performance. It is unlikely, however, that the new rule will dramatically alter the mix of fixed and performance-based compensation. Institutional investors and activist shareholders are expected to resist any significant changes in the composition of executive compensation. According to representatives of Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), a proxy advisory firm, “Investors will continue to expect that executive pay programs emphasize performance-based incentives . . . any board that eliminates or reduces performance-conditioned incentives in favor of guaranteed or highly discretionary pay is going to face investor backlash.” 25 See David Kokell et al., U.S. Tax Reform: Changes to 162(m) and Implications for Investors, Harv. L. Sch. F. on Corp. Governance & Fin. Reg. (Jan. 25, 2018), https://perma.cc/DU2F-CMS2. For the debate concerning paying executives for performance, compare Dan Cable & Freek Vermeulen, Stop Paying Executives for Performance, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Feb. 23, 2016), https://perma.cc/9V25-YXAB (arguing that financial incentives, such as bonuses and direct rewards, might damage performance), with Ira Kay & Lane Ringlee, Continue Paying Executives for Performance: A Rebuttal to the HBR Article “Stop Paying Executives for Performance,” Pay Governance (May 19, 2016), https://perma.cc/7FZV-EB23 (arguing that the incentive-based pay for performance model has created enormous value for shareholders).

Thus, our analysis indicates that companies are unlikely to voluntarily reduce their executive compensation levels. 26 Another important aspect of the recent tax reform is related to its potential impact on the incentives for founders and other executives to keep their companies private longer. A full analysis of this question is beyond the scope of this Essay. For present purposes, however, it will suffice to make two preliminary comments. First, as we have shown in this Part, the reform is unlikely to substantially impact the amount of a CEO’s compensation at a public firm. Therefore, as long as the CEO maintains a limited equity stake in the company, and her compensation stays substantially the same, the reform is unlikely to have a significant effect on the CEO’s financial incentives to take the firm public. Second, even if the reform is likely to increase the tax obligations of public firms relative to private firms, the decision to go public is a complex one that is likely to be motivated by other considerations. See Lucian A. Bebchuk & Kobi Kastiel, The Untenable Case for Perpetual Dual-Class Stock, 103 Va. L. Rev. 585, 624 (2017) (noting that “[f]or founders with limited personal wealth, accessing the public market at some point is commonly critical to scaling up their companies and creating liquidity for themselves and early investors”). This analysis is supported by novel empirical evidence that we will present in the next Part.

III. What Companies Disclose

Under the current SEC disclosure rules, shareholders will not be able to learn the actual cost of the disallowed deductions under section 162(m). This is because companies are not obligated to report the magnitude, or quantify the actual costs, of the disallowed deductions. All that is required of companies is to disclose “[t]he impact of the accounting and tax treatments of the particular form of compensation.” 27 Executive Compensation, 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(b)(2)(xii) (2017).

To meet this requirement, companies could verbally describe, in very general and broad terms, the rules under section 162(m) and their potential implications, without providing any quantification of the disallowed deductions. Of course, this does not necessarily have to be the case. Companies could go beyond the minimal disclosure requirements and provide a detailed account of the disallowed deductions under the amended section 162(m).

To ascertain what information companies have furnished to their shareholders in the first fifty days following the enactment of the TCJA, we analyzed a hand-collected dataset of all proxy statements with disclosures regarding the amended § 162(m) that were filed with the SEC between December 23, 2017 and February 10, 2018 by companies that paid one or more of their executives more than $1 million in 2017. 28 We did not include several companies that only had one executive that received slightly more than $1 million because the disallowed deduction may not be material for these companies. We included in this dataset only those proxy statements that referred to the amended section 162(m) under the TCJA. Our dataset comprises fifty-eight companies. 29 The companies in this sample are the following (in the order of the publication date of the proxy statements): Apple Inc.; MTS Systems Corporation; Varian Medical Systems, Inc.; Fleetcor Technologies, Inc.; Franklin Resources, Inc.; TD Ameritrade Holding Corporation; Beacon Roofing Supply, Inc.; Deere & Company; Johnson Outdoors, Inc.; The Walt Disney Company; Lee Enterprises, Inc.; Sanderson Farms, Inc.; Macom Technology Solutions Holdings, Inc.; Matthews International Corporation; National Holding Corporation; Alico, Inc.; AECOM; Viacom Inc.; Nordson Corporation; Johnson Controls International PLC; Cubic Corporation; AmerisourceBergen Corporation; TE Connectivity, Ltd.; Shiloh Industries, Inc.; BPT Apartment Corporation; Cabot Microelectronics Corporation; Helmerich & Payne Inc.; Berry Global Group, Inc.; Tetra Tech, Inc.; REV Group, Inc.; Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Applied Materials, Inc.; Jack in the Box Inc.; Civitas Solutions, Inc.; NCI Building Systems, Inc.; Hovnanian Enterprises, Inc.; Hologic, Inc.; Nuance Communications, Inc.; Starbucks Corporation; Adient PLC; Fair Isaac Corporation; F5 Networks, Inc.; Cabot Corporation; Analog Devices, Inc.; Datawatch Corporation; Quanex Building Products Corporation; Maximus, Inc.; Hurco Companies, Inc.; Coherent, Inc.; The Cooper Companies, Inc.; The Toro Company; Advaxis, Inc.; ABM Industries Incorporated; Tesla, Inc.; VeriFone Systems, Inc.; Agilent Technologies, Inc.; Keysight Technologies, Inc.; OMNOVA Solutions, Inc. The list of proxy statements is available on the Stanford Law Review website at https://perma.cc/5GJT-WJM4. High-profile companies covered by this dataset include Apple, Tesla, Disney, Applied Materials, AECOM, and Viacom. As this is an analysis of a sample of proxy statements, we cannot rule out the possibility that proxy statements that are not included in this dataset may have different disclosure practices. Although the companies in this sample vary in their characteristics, the disclosures regarding § 162(m) are very similar, as detailed in the analysis below.

Our analysis shows that none of the companies that had disallowed deductions in 2017 disclosed information about the quantum of their disallowed deductions. Notably, companies only provided a verbal description of the rules of § 162(m), and whether specific compensation schemes were designed to qualify for the exceptions of the old § 162(m).

The analysis also revealed companies’ approaches regarding the potential impact of the TCJA and how compensation committees will consider the nondeductibility of executive compensation. Most companies (86%), including Apple, Disney, and Applied Materials, stated that they might grant nondeductible compensation, if doing so is in the best interest of the company and its shareholders. These companies typically noted that the nondeductibility of the compensation is only one of the factors taken into consideration. They further maintained that the compensation committee should be flexible when awarding nondeductible compensation, if the committee finds that this compensation is consistent with the goals of the company’s executive compensation program. Some of these companies remarked on the importance of providing a compensation program that attracts, retains, and rewards executive talent. A minority of the companies (14%) described the new rules under the amended section 162(m) without stating the considerations of the compensation committee regarding compensation policies under the new rules.

Equally important, no company indicated that it would consider decreasing the executive compensation because of the increased tax cost. A minority of the companies (24%) noted that they will assess the impact posed by the amended section 162(m) and other changes contained in the TCJA on their executive compensation programs. Specifically, one company noted that the tax changes “could impact future pay practices.” 30 See AECOM, Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A), at 53 (Jan. 18, 2018). Another company noted that “[t]hese changes could, but may not, impact compensation decisions for fiscal 2018 and beyond.” 31 See Hologic, Inc., Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A), at 40 (Jan. 26, 2018).

Therefore, our analysis of all relevant proxy statements filed after the TCJA was enacted shows that companies have not disclosed the quantum of the tax cost of executive compensation. As the tax cost becomes more significant under the amended section 162(m), the information concerning the quantum of this cost will become more important for shareholders. Nonetheless, as our analysis reveals, companies will likely continue the current practice of providing only a verbal discussion of the rules under section 162(m). Our analysis also shows that companies will likely incur the increased tax cost without reducing their executive compensation levels.

IV. Policy Implications

Our findings have significant implications for policymakers. Subpart A presents the case for making the tax cost of executive compensation more transparent. In particular, it explains why shareholders are unlikely to be able to estimate the tax cost of executive compensation by themselves and why it is more efficient for the company to disclose this information. Subpart B puts forward a proposal for regulatory changes that could be adopted by the SEC.

A. The Case for Making the Tax Cost Transparent

So far, we have shown the following: (i) the TCJA is expected to significantly increase the tax cost of executive compensation in many public companies; (ii) these companies are likely to incur the higher tax cost without reducing their executive compensation levels; and (iii) these companies will not disclose the quantum of the increased tax cost of executive compensation to their shareholders. Yet the combination of these elements does not necessarily justify a regulatory intervention. For example, one could argue that even if companies do not disclose this information, shareholders should be able to estimate the tax cost by themselves.

There are a few reasons to make it imperative for companies to disclose the tax cost of executive compensation. To begin, a significant part of the compensation that many companies will pay in 2018 and the following years might be grandfathered in. Thus, as companies are not required to disclose the amount of executive compensation that is grandfathered in, shareholders will not be able to estimate the tax cost of executive compensation for the coming years.

In a few years, it is likely that most, or even all, of the grandfathered arrangements will expire. Nevertheless, shareholders might still suffer from asymmetric information and encounter difficulties while attempting to estimate the tax cost of disallowed deductions under section 162(m). For example, shareholders would have to assume that if the deductions were allowed, the deductions would reduce the taxable income subject to the corporate tax rate, which is assumed to be 21%. This assumption, however, does not hold in some cases, and shareholders may not have the necessary data to make informed adjustments.

Moreover, it might be costlier for each shareholder to calculate the tax cost of executive compensation separately. 32 For an economic justification of mandatory disclosure grounded in the notion that firms are the lowest cost obtainers of most information relevant to securities valuation, see Paul G. Mahoney, Mandatory Disclosure as a Solution to Agency Problems, 62 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1047, 1048-49 (1995). Firms already have the information needed to quantify the tax cost of executive compensation, and it would be more efficient for each company to provide the tax cost information to its shareholders in a unified fashion. 33 See Lucian A. Bebchuk & Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Executive Pensions, 30 J. Corp. L. 823, 853 (2005) (arguing that “[f]irms generally already have low-cost access to the information necessary to value retirement benefits” and that “firms can obtain this information at lower cost than can shareholders or researchers”); Allen Ferrell, The Case for Mandatory Disclosure in Securities Regulation Around the World, 2 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 81, 111-15 (2007). We do not expect that the mandatory disclosure, which we propose in subpart B, would impose any significant costs on firms. This is because companies are already required to calculate whether expenses are deductible or not for their federal tax filings. 34 Under the federal tax filing requirements, corporations are required to report the total deductible compensation of their executives, see IRS Form 1120, line 12, and also the details of the deductible compensation paid to each of the executive, see IRS Form 1125-E. As companies know the exact disallowed deduction and the tax that would have been saved if the expenses were deductible, disclosing this information would entail no additional costs.

Finally, we note that disclosure rules already require companies to disclose the amounts of tax reimbursements and gross-ups concerning golden parachutes and other personal benefits. 35 17 C.F.R. §§ 229.402(c)(2)(vii)(B), (c)(2)(ix)(B), (t) (2017). From an economic perspective, there is no difference between the following situations: (i) the executive pays a tax bill, and the company reimburses him for the amount he or she paid; and (ii) the executive does not pay such a tax bill, and the company pays that bill directly. Under the current disclosure rules, however, only the former amount is reportable. Similar to the disclosure of tax-reimbursements and gross-ups, the tax cost of disallowed deductions under section 162(m) should also be disclosed.

B. The Proposed Regulatory Response

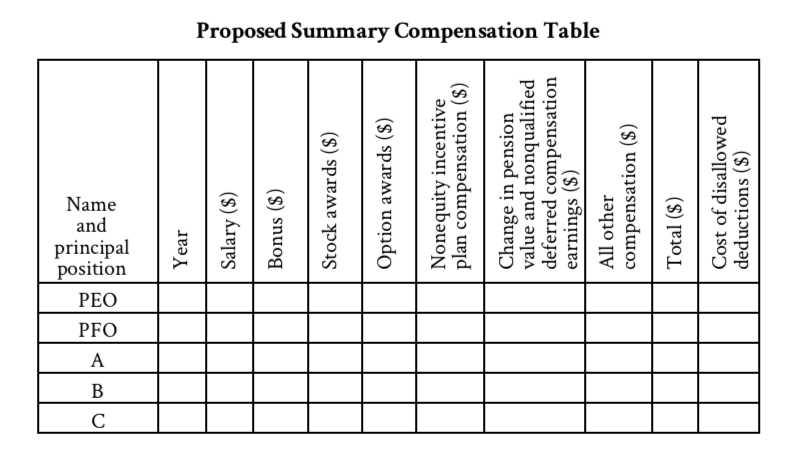

This Essay proposes that the SEC adopt disclosure requirements that would compel public companies to make the tax cost of executive compensation fully transparent. This disclosure should be made in two parts of the proxy statement. First, the tax cost from the compensation of the CEO, CFO, and the other highest earners should be provided in a new column in the Summary Compensation Table, as this table “provides, in a single location, a comprehensive overview of a company’s executive pay practices.” 36 See SEC, Executive Compensation, https://perma.cc/NT99-MVH6 (archived Apr. 29, 2018). Appendix I demonstrates the proposed changes to the Summary Compensation Table.

Second, the part of the proxy statement that currently discloses “[t]he impact of the accounting and tax treatments of the particular form of compensation” 37 See Executive Compensation, 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(b)(2)(xii) (2017). should also provide the material information about the tax cost from disallowed deductions under section 162(m) that cannot be found in the Summary Compensation Table. This information should include the tax cost from compensation to persons who are no longer “covered employees” in the last year, 38 Covered employees from previous years that are not employed in the reported fiscal year are not included in the Summary Compensation Table. as well as any other material information regarding the tax cost of disallowed deductions. The SEC may also consider making it obligatory for firms to disclose the increase in overall tax cost from disallowed deductions under section 162(m) in comparison to 2017. 39 As noted above, companies do not currently publish the information about the tax cost in 2017.

The SEC should amend the disclosure rules in 2018 so that the proxy statements filed next year will include this material information. Shareholders’ ability to initiate changes to compensation practices, which will become more expensive because of the changes in tax law, depends on making information about these costs transparent.

It is important to note that our proposal is not merely a technical amendment to the company’s proxy statement. The exclusion of tax cost from the analysis of executive pay might lead shareholders to underestimate the actual costs of executive compensation. 40 Cf. Lucian Bebchuk & Jesse Fried, Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation 95-111, 135-36 (2004) (explaining how managers obtain substantial value from pensions, deferred compensation, and post-retirement perks, and that much of it is never reported in the compensation tables filed with the SEC); Bebchuk & Jackson, supra note 33, at 854 (explaining that the exclusion of pensions from analysis of executive pay has led shareholders to underestimate the magnitude of executive compensation). By correcting such misconceptions, these disclosure requirements might enable shareholders to scrutinize compensation arrangements more effectively, and, if necessary, press companies to reduce their compensation levels or adopt other arrangements that are better aligned with the interests of shareholders.

Conclusion

This Essay explains how the TCJA is expected to significantly increase the tax cost of executive compensation in many public companies. It presents evidence showing that public companies are likely to shift the higher tax cost to public shareholders without reducing executive compensation levels and without disclosing the quantum of the tax cost of executive compensation to their shareholders. To address this insufficient disclosure, we propose that companies should be obligated to make the tax cost of executive compensation transparent to their shareholders, and we outline a concrete proposal for disclosure requirements that could be adopted by the SEC.

The case for requiring the disclosure of the tax cost of executive compensation is compelling. Such disclosure would significantly improve the accuracy of investor information regarding the overall cost of executive compensation. This could also improve shareholders’ scrutiny of compensation practices. The compliance costs for companies would be minimal. Therefore, there is no reasonable basis to oppose such disclosure requirements. The SEC should consider amending the disclosure rules in 2018 so that the proxy statements filed next year will include this information.

* Kobi Kastiel is Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University; Research Fellow, Harvard Law School Program on Corporate Governance. Noam Noked is Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Appendix I